In movies, investors are often seen analyzing charts of numbers or reading The Wall Street Journal. But while data plays a key role, investing often comes down to what happens in our heads.

In movies, investors are often seen analyzing charts of numbers or reading The Wall Street Journal. But while data plays a key role, investing often comes down to what happens in our heads.

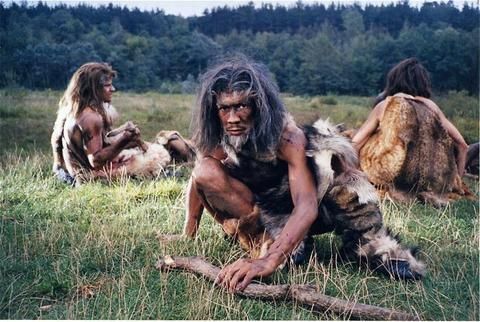

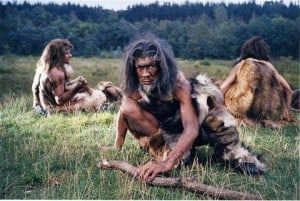

The truth is, human beings are not naturally “wired” for investing. We evolved in caves and jungles – and nothing in our ancestral environment prepared us for the complex financial decisions we all face today. Quite the opposite: the instincts that served us so well as hunters and gatherers can utterly devastate our investment portfolios.

Best Practices for the Intelligent Cave Man

Harvard MBA John T. Reed discusses the problem in a web article about best practices for intelligent real estate investors:

…human brains evolved during caveman days to deal with the best practices for the intelligent cave man. Those best practices included safety in numbers, flight is usually better than fight, better safe than sorry when it comes to physical injury if you have no HMO, if something happens twice it’s best to assume it’s a permanent pattern, vivid dangers like being stomped by a mammoth are more important than abstract dangers like interest rates going up, and so on.

What is logical for investors is often the opposite of what is logical for being a caveman. In the caveman world, all the dangers were physical: poison plants, attacks by animals or other tribes, falling off a cliff, fire, etc. In the investment world, caveman best practices like the herd instinct can be very bad.

That’s why shrewd investors need to be aware of their problematic instincts and devise strategies to counteract them. Here are six of the most insidious instincts that threaten your portfolio:

1. Confirmation Bias

Very simply, confirmation bias refers to the tendency we all have to pay attention to data that supports what we believe and ignore data that contradicts it. For instance: if you support gun control policies, you will likely pay more attention to studies about gun violence (because they reinforce what you already believe) and less attention to reports of gun control policies precipitating higher gun violence (because it conflicts.)

Confirmation bias is a dangerous instinct for investors to be swayed by, because often the most crucial data is precisely that which contradicts our beliefs. Investors NEED to hear unpleasant news so they can change their strategies in time to avoid being wiped out. Adopting a “head in the sand” posture toward unflattering or ego-bruising data is what causes many investors (big and small) to suffer needless losses in the market.

2. Mental Accounting

Mental accounting is a term behavioral economists use to describe the way humans divide money into arbitrary and self-defeating mental categories. In my previous article on mental accounting, I wrote about a version of this thinking that plagues investors: “money you can afford to lose.”

Investors are, as a group, highly prone to the “money you can afford to lose” variant of mental accounting. Under this notion, investors view some arbitrary amount of their investment capital as “play money” which they feel comfortable squandering on speculative and uncertain things. At first glance, this has the makings of sensible decision making. It seems prudent to clearly delineate between money that matters and money that doesn’t.

The problem, of course, is that “money you can afford to lose” is a purely mental creation. An economist would say that true financial rationality dictates never putting money somewhere that it was likely to be lost, and that no amount of mental maneuvering would make this an acceptable fate for any amount of money in your possession.

The takeaway here is that money is fungible: it’s ALL money, no matter which random categories you divide it into. Be on the lookout for mental accounting and the many ways it can poison your investment choices!

3. Anchoring

Anchoring happens when we rely too heavily on just one or two pieces of information in our decision making. For instance, a person seeking to buy a used car might focus all her attention on the odometer reading or the year the car was built while ignoring other important factors (emissions testing, maintenance records, engine soundness, etc.).

Investors can be misled in similar fashion, such as by evaluating stocks solely in terms of P/E ratios or management fees whatever their pet metric happens to be. The smarter approach is evaluating investment choices holistically, taking into account as many relevant factors as possible to gain a comprehensive understanding of risk and reward.

4. Sunk Cost Fallacy

Of all the cognitive biases, none is more frequently experienced by investors than the sunk cost fallacy. Very simply, the sunk cost fallacy states that past expenditures should have no bearing on future decisions. This is contained in cultural slogans like “don’t throw good money after bad” or “there’s no use crying over spilled milk”, or even in sports, when coaches admonish their players to “forget about the last play, focus on the next play.”

Investors constantly allow the sunk cost fallacy to get in the way of sensible investing. In some sense, it’s quite understandable: no one likes admitting the “winning move” they poured $10,000 into was actually a huge bust. But instead of facing the truth and emotionlessly cutting their losses, many investors cling to failed investments, telling themselves “eventually it’ll go back up to the real price” or “it’s not a real loss until I sell.” These statements are nothing short of delusional. Even if a fallen stock later appreciates, it is simply an unrelated increase, not “going back up.” Furthermore, losses are real the moment they accrue – all holding on does is delay the painful realization of what already took place.

5. Clustering Illusion

One of the uniquely fascinating features of the human brain is its ability to find patterns in what it perceives. In fact, it’s more than a mere ability – the brain is literally wired to look for patterns whenever it can, always seeking to make order out of chaos and boil the world down into simple rules. But as undeniably useful as this is, it can lead us astray when we read patterns into situations where none exist.

For instance: in our evolving caveman days, it was probably wise to assume any bear that crossed your path was a threat and avoid them in the future. Acute pattern recognition was highly beneficial when most human dangers were physical. But it is less useful when studying reams of abstruse data or looking for similarities in the performances of different stocks – many of which have little, if anything, in common with one another. Just because your tech mutual fund went down last August doesn’t mean all tech stocks tank every August, for example.

6. Bandwagon Effect

Following the crowd made a lot of sense in caveman days. If everyone in the village avoided berries from a certain tree, it probably had more to do with the berries being poisonous than with that week’s food trends. Safety in numbers was a prevailing belief because it served our ancestors well in many of the situations they encountered. Today, though, the majority can be (and often is) dead wrong.

Look no further than Warren Buffett, who attributes his massive investment fortune to “being fearful when others are greedy, and greedy when others are fearful.” This excellent saying is a testament to contrarianism, or deliberately ignoring what the masses are doing to discover a better way.

The Takeaway About Caveman Instincts

It’s important to remember that these caveman instincts are not “irrational”, per se. They became instincts precisely because they once served us so well. Rather, the points is that the caveman instincts we all still possess are suited for a much different environment than the one we now inhabit. Investors are not primarily concerned with snakes or storms or famines – the types of physical and primal dangers we confronted ancestrally. We are much more concerned with abstract or financial dangers that the brain is not innately wired to understand.

Have you ever threatened your portfolio by falling for one of these caveman instincts?

Jay Cross is the creator of The Do-It-Yourself Degree. Jay teaches independent learners how to graduate in half the time for pennies on the dollar by testing out of courses.

Editor: Clint Proctor